Tailored to customers’ specifications, Sacmi’s highly automated production flow and warehouse logistics management systems take ceramic production a step closer to a service industry capable of offering efficiency and flexibility for both customers and the market.

Tailored to customers’ specifications, Sacmi’s highly automated production flow and warehouse logistics management systems take ceramic production a step closer to a service industry capable of offering efficiency and flexibility for both customers and the market.

Like any industrial process, ceramics has clearly defined production stages consisting of grinding, spray drying, drying, pressing, decoration, firing, transport and storage. Until recently, optimising these individual steps was the only possible strategy for making the production process more efficient, for maintaining adequate margins and for responding to the changing needs of companies and the market.

But with the latest technological advances, attention has now shifted away from optimisation of individual stages towards integrated and efficient management of complete production flows.

The really innovative aspect, however, is the new approach to the concept of production flow. Until recently, apart from cutting processing costs the only option available to ceramic companies was to separate the various stages by installing micro or macro storage units, which serve to compensate for the differences in average efficiency of some of the processes and protect against line stoppages.

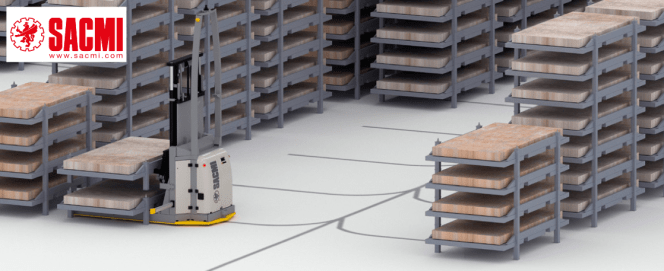

In other words, the only intralogistics approach involved creating intermediate storage units in given areas or stages of the plant, while the direction and order of these flows remained fixed, resulting in limited flexibility. The problem has been partly mitigated with the advent of laser-guided vehicles (LGVs), which allow for greater production flexibility.

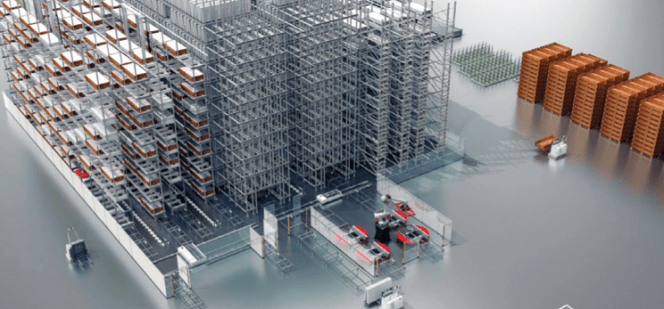

From the point of view of a major technology supplier like Sacmi, which for more than twenty years has been a market leader in the design of plant supervision systems, the revolution in logistics is closely bound up with the production of plants for large-size slab and panel production. These are both new products in their own right as well as semi-finished materials that serve to produce sub-multiples, strips and furnishing accessories such as tables and kitchen worktops, which means that they come in a wide range of thicknesses and finishes.

From the perspective of the ceramic producer, this has led to a sharp increase in the number of individual products or SKUs, which together with a smaller average production batch size (now 100 square metres or less) has led to a further improvement in technological quality. Clearly, SKU proliferation has made it necessary to drastically reduce warehouse stocks and has led to a series of seemingly incompatible needs: producing a larger number of products in smaller batches, using a small number of production lines, meeting delivery times and coping with the ever greater fragmentation of demand.

The Sacmi solutions for intralogistics 4.0 have well defined characteristics. They offer a choice between self-supporting stackable warehouses, shelving warehouses and automatic intensive warehouses equipped with transfer elevators. The maximum degree of optimisation is often achieved through a combination of multiple solutions or, depending on incoming and outgoing material flows to and from other factories, multiple production units or suppliers.

The starting point is always a joint analysis carried out together with the customer of the complexity of the situation together with mapping of the implemented production flows. How many SKUs are there? How is demand from customers and the market structured? What improvements in efficiency can be made by re-engineering production and flows?

These are just some of the key questions that Sacmi is able to address right from the design stage through precise production simulations.

At the same time a number of highly customisable solutions are available: the production of sub-multiples before rather than after firing, the use of vertical or horizontal warehouses, combining maximum automation (intensive warehouses served by transfer elevators) with floor-level storage islands, all served by automatic handling units that sort the right material at the right time. Based on projects actually commissioned from Sacmi rather than abstract concepts, this approach could become the benchmark solution for improving the efficiency of each individual operational and production stage.

Clearly, however, all of this requires a radically different approach to operations management and it is normally necessary to carry out an in-depth analysis of flows and propose solutions for improvement.

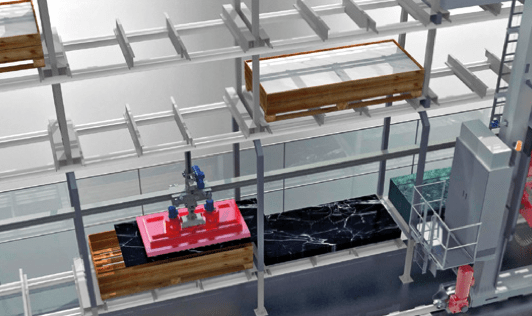

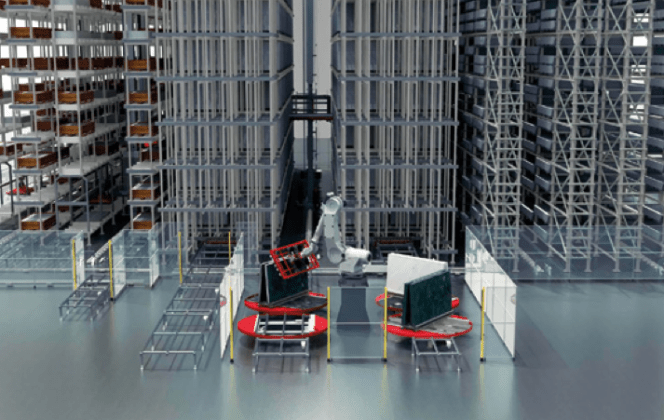

Robotised picking islands lie at the heart of the system for adding value to the proposed solution. This can easily be understood by looking at a classic example: an order of a certain number of square metres of large-size floor or wall tiles that never or almost never correspond to the standard capacity of a crate, stand or pallet. However, this new approach is not limited to large and expensive decorated panels. The use of picking islands to create composite orders is a solution that improves efficiency for all kinds of products, including sub-multiples. Essentially, it is a new production approach that takes ceramics a step closer to a service platform model rather than a classic manufacturing process.

In practical terms, Sacmi configures picking islands in such a way as to allow products to be transferred between crates and stands. It also adopts an upstream quality control system for containers and supports (typically made of wood with the possible presence of nails, defects and asymmetries) used for storing and loading tiles and a system for automatically introducing and securing the tiles inside the crates.

Sacmi’s entire approach fits in with the concept of complete plant engineering, in which operations are performed not in sequence but as part of combined cycles. In this approach, an LGV entering a ware- house needs to be associated with a corresponding exit phase. The deposit bays must be organised in such a way as to make these operations rapid and effective while eliminating downtimes. After this, there are many possible solutions for vehicles and warehouses, and the key factor is the ability to develop all aspects together with the customer, who will consequently be equipped with an advanced factory management system.

This is important because the only way to analyse and manage flows is to adopt a plant supervisor that allows the OEE (overall equipment effectiveness) indices to be integrated with MES or order scheduling functions interfaced with the customer’s ERP. At the same time the information flow is managed in such a way as to provide feed-back on production and consequently identify and resolve critical issues at source.

The solution that Sacmi has been offering the market for several years is called H.E.R.E. (Human Expertise for Reactive Engineering), a latest-generation plant controller that stands out for its ability to give priority to different functions and goals, such as compliance with delivery times, cost optimisation, etc.

The assembly-to-order configuration, a perfectly natural approach for an industry like ceramics that by its nature has to cope with a certain degree of rigidity upstream of the process, is just one of the configurations possible with a system of this kind. It can even be improved by going as far back as the initial stages of the process upstream of shaping. This has been demonstrated through the presentation of Deep Digital, a solution that digitally integrates all slab shaping, glazing and decoration operations.

Identifying homogeneous classes of products at this level to reprocess on a just-in-time basis could prove not just possible but also relatively simple. In other words, in the near future, the command to produce an additional 3 square metres of black lappato slabs for a given customer could be given simply with the click of a mouse and without any adverse impact on plant efficiency or profitability.

More at: https://www.sacmi.com or https://www.sacmi.it

By Roberto Pelliconi, Sacmi, Imola, Italy. This article first appeared in Ceramic World Review CWR 133/2019